José Solana

The Gathering at Café Pombo

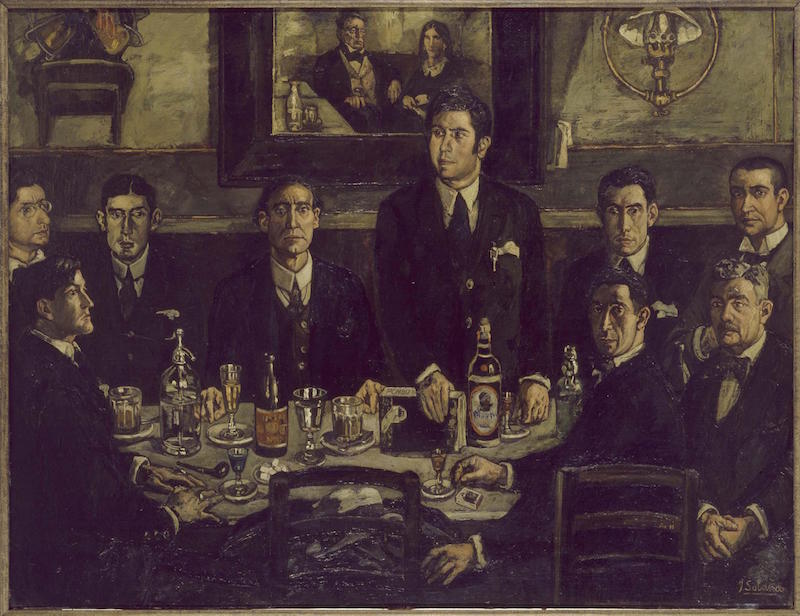

During the 19th century and until the Spanish Civil War, cafés increasingly became all-important institutions in the cultural life of Madrid and other Spanish cities with the gatherings they hosted. The foremost café became the drinking establishment and coffee shop Café Pombo, located on Calle Carretas in Madrid, just off Puerta del Sol, and from 1915 onwards it was the venue for one of the best known literary gatherings, organised every Saturday by novelist Ramón Gómez de la Serna and frequented by figures from the breadth of Spain’s avant-garde scene.

A record of its thronging activity exists in the numerous articles and publications by the aforementioned José Gutiérrez Solana, for instance Pombo (1918) and La sagrada cripta de Pombo (The Sacred Crypt of Pombo, 1924), but undoubtedly it is José Gutiérrez Solana’s 1920 painting that gives form to the most iconic images of such gatherings. In the picture, some of the pre-eminent intellectuals present at these occasions are portrayed, for instance Gómez de la Serna — stood in the centre of the scene — with Solana, Manuel Abril, Mauricio Bacarisse, Tomás Borrás, José Bergamín, José Cabrero, Pedro Emilio Coll and Salvador Bartolozzi.

Macro photography reveals how Solana worked on the background by adding layers which, at some point, were scraped with a palette knife before the next was added. This way of painting, with its combination of sharp contrasts of material and colour with strong impastos and oily shades applied with liberal amounts of binding agent, is characteristic of Solana’s artistic technique.

Additionally, this study enables a precise study of the alterations and damages suffered by the work, leaving a detailed record of its current state of conservation. In this case, the craquelure can be clearly discerned and is visible mostly in the black areas.

Under ultraviolet light, the first thing to catch the eye in Solana’s painting is the layer of varnish: the blue-greenish fluorescence, which appears to spread randomly. That said, when comparing this image with the one taken with visible light we can see how, in the latter, the shiny varnish finish is noticeably uniform, with the contrast between both images responding to Solana’s use of different binding agents, oils and varnishes — in different amounts and with different forms of application — according to the object being painted.

Thus, the suits, glasses, flesh tones and mirror surface in the background show different fluorescent responses given that they are painted with unequal mixes of binding agents and pigments. Although this is repeated across the entire canvas, it is particularly interesting to observe this phenomenon by zooming in on the suit material of Gómez de la Serna, who is shown standing in the centre of the composition with a fountain pen in his pocket, and compare it with his face or the bottle between his hands.

This technique also offers the chance to see previous restorations, distinguished from the original paint by not showing fluorescence and displayed in another colour. An example of this is seen in the top right corner, where the chromatic reintegrations are a reddish colour, or in Mauricio Bacarisse’s ear, depicted just to the right of Gómez de la Serna.

In José Gutiérrez Solana’s paintings, the extraordinary thickness of the layers of oil paint is such that infrared radiation, despite being greater in wavelength than visible and ultraviolet light, is not able to penetrate them.

Nevertheless, the technique does provide key data on the artist’s working method; for instance, around José Cabrero’s head, located to the left of Gómez de la Serna, it reveals strokes that do not correspond under visible light, referring instead to an underlying composition. X-ray imaging is necessary here to check the original intention.

X-rays reveal the existence of a religious painting concealed under the figures of Café Pombo. This would suggest, therefore, that Solana re-used a canvas upon which he had already painted, vertically, an altar scene. Given the high definition of some of its elements through x-ray imaging, we can assume that he rejected the work at a considerably advanced stage.

In the centre an altar covered with a cloth falling down its sides can be discerned, and upon which there are three candleholders and various sacred vessels — perhaps a chalice, paten and pyx — along with two heads which, judging by the pained expression on one of them, could be reliquary busts of martyrs.

In the background we can make out an altarpiece with a figure in the centre, possibly a virgin. In front of the altar there is a kneeling figure leaning on one of his hands and covered in religious robes.