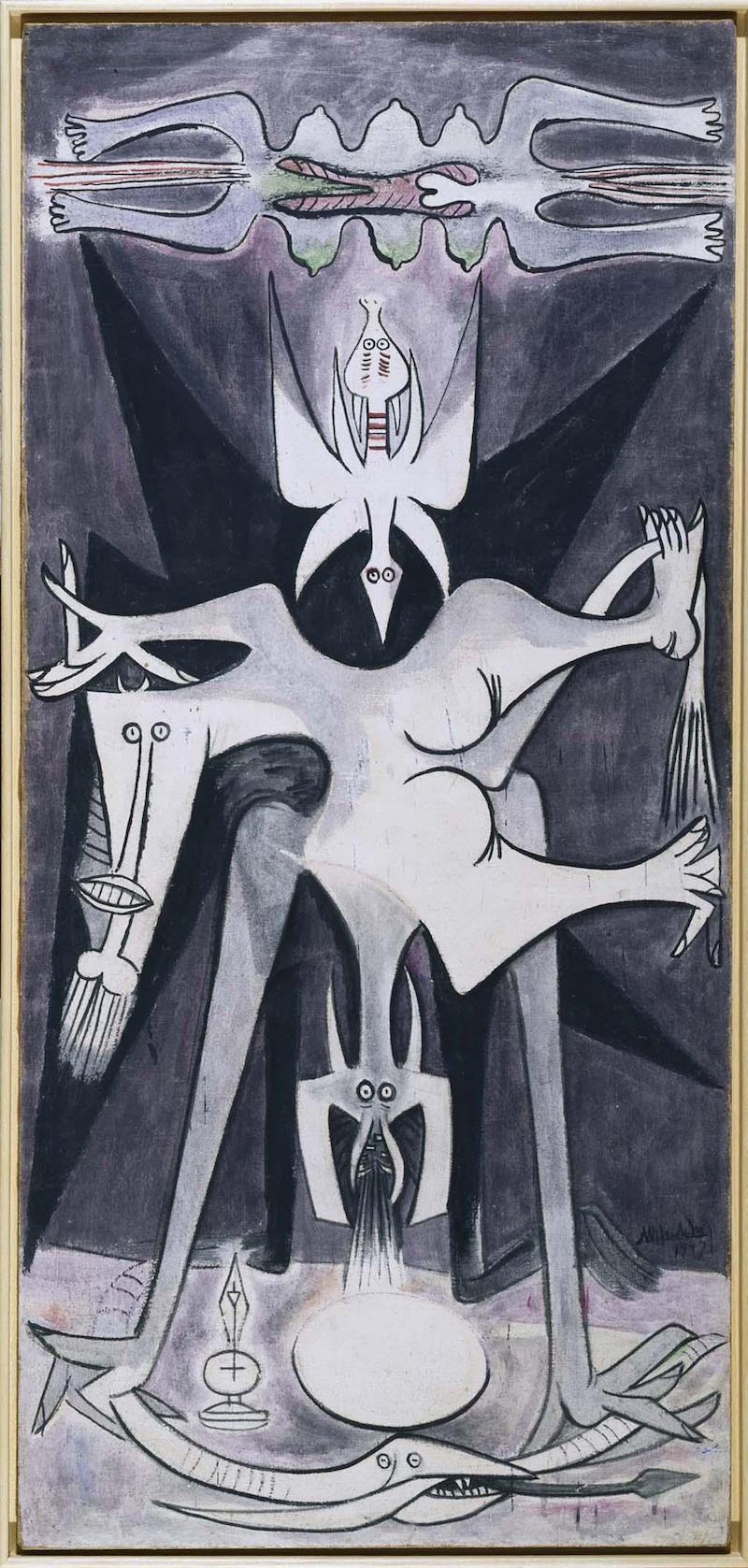

Wifredo Lam

Nativity

Wifredo Lam moved to Paris in 1938, where he came into contact with the Surrealist group, before returning to the Caribbean at the onset of the Second World War with André Breton, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Victor Serge and other members of the said group. In 1941 he settled in Havana and began a pivotal series of works in which he represented human and animal forms, drawing inspiration from African sculpture, combined with a symbolic landscape with reference points taken from the boundless nature of the Caribbean. In Nativité (Nativity) he goes back to a recurring theme in the output of the time: the myths and rituals stemming from Santería, in which the tradition of the orishas, deities from the Afro-Cuban religion, merge with narratives and iconography from Christianity. The image of the woman-horse, the bird and the snake are motifs reflecting his interest in totemic forms of African imagery that tie in the Surrealist penchant for mixed beings with nature and culture. The use of sombre colours, which dominate a synthetic composition, fragmented into planes, extolls the workmanship of his mature work.

For the work’s support, Lam chose thick, rough hessian fabric, more frequently used to make sacks than paintings. Under this light, we can see the coarseness of its threads on the outer edges, where the layers of colour don’t reach.

Through the detail afforded by macro photography we are able to gain some insight into the artist’s creative process. Firstly, he applied a homemade white primer, a base which he left exposed in some areas and in others covered it with fine layers of colour. This base provides the light that emerges from the background of the painting, similar to stained glass, which was a huge influence on Lam’s technique. If we zoom in on the figure at the top with six breasts, we can see how highly fluid layers were overlapped on the first base and were initially blue, then green, and fuse together with an effect similar to a watercolour.

Finally, of note is the powerful and solid black line that skirts the main image and adds weight to its contour. As with the rest of the figures, it adds huge unity to the composition.

Generally, the lines of the drawing are executed in different layers: the first with more liquid greys and the definitive ones with a heavy brushstroke of colour. The result is a heavy matte paint, with an appearance related more to a water-based approach than oil, on a very coarse base.

Under this type of light the texture is foregrounded, and the white primer can be distinguished as it mixes with the large fibres of the hessian.

In terms of the work’s conservation, the hessian support is particularly hygroscopic; that is, it reacts a great deal to changes in temperature and moisture. These movements affect the layers of paint, particularly in the background, producing more craquelure and even micro-losses.

This special feature can be perceived in details with maximum resolution, for instance on the bottom left wing of the bird with two heads, where paint losses and fissures can be discerned on the canvas.

Ultraviolet light makes it possible to distinguish between past interventions on the work, and according to variations in the fluorescence that shows up on the surface of the painting. In Nativité we can discern, in a hugely opaque, dark-violet tone, the liberal colour retouching that covers the paint losses.

Although colour reintegration spreads across the whole outer edge, it is particularly interesting to observe the inside left corner. In this area, as indicated by its disparate response to fluorescence, different overlapping chromatic reintegrations are revealed, and were made at different times and with different kinds of materials.

Furthermore, some of the colour splashes made while the painting was being created were covered by colour touch-ups on subsequent restorations, and were later removed, leaving a visible trace under ultraviolet light.

Digital infrared photography penetrates the surface of the painting and shows up underlying layers. For instance, on the left-hand margin we can see off-white marks that relate to the stucco, used under chromatic retouchings to fill and even out paint losses, as well as to seal the delicate edges of the hessian.

As the piece was executed with very fine layers of paint, the lines of a preliminary drawing can be discerned under natural light. Nevertheless, via the infrared technique, these can be appreciated with greater clarity, for instance in the area of the right claw holding the snake.