Pablo Picasso

Musical Instruments on a Table

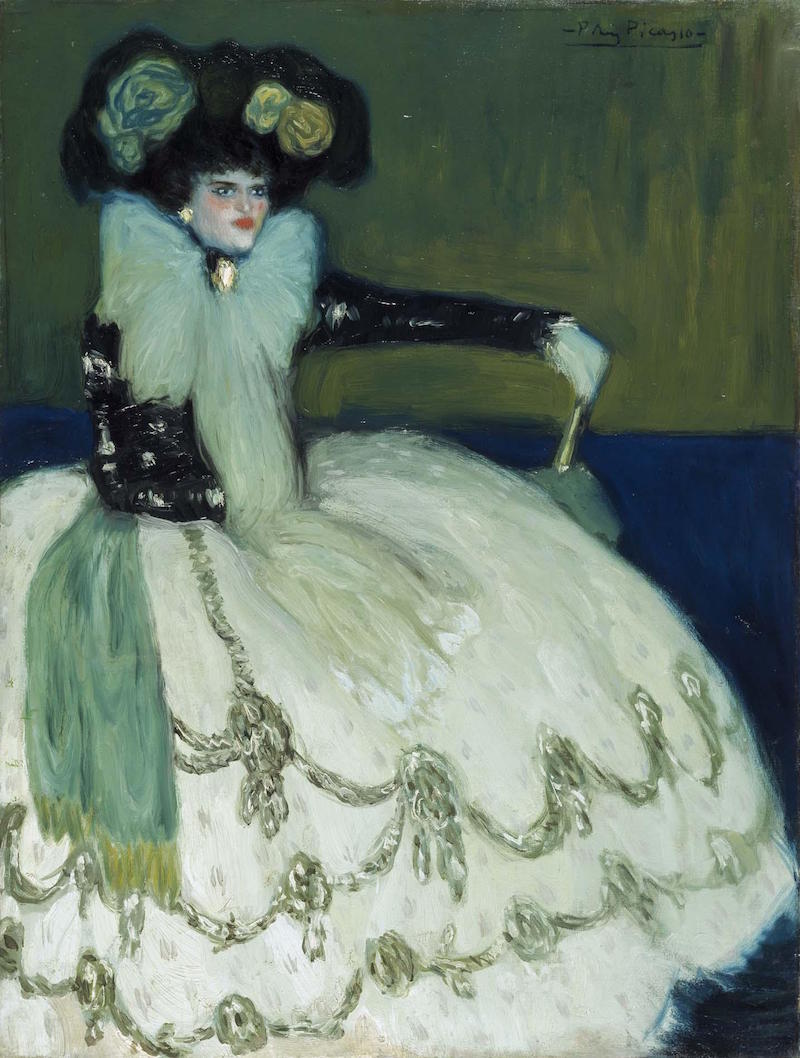

Between January and May of 1901, after an initial spell in Paris the previous year, Picasso took up residence in Madrid. It was there that he would come into contact with writers and artists from the Generation of ‘98, with whom he worked on the journal Arte Joven (Youth Art), operating as artistic director. During those months, in addition to illustrations for the publication, Picasso produced a series of courtesan portraits with myriad references ranging from modernism – with which he had become acquainted in Barcelona – to Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, the brushstrokes of El Greco and even Velázquez, from whom he borrowed the composition from his Queen Mariana of Austria portrait.

Picasso sent Mujer en azul to the General Exhibition of Fine Arts in Madrid that same year, where it went unnoticed. Before the show concluded he had already left Madrid to prepare his first solo show in Paris, and the work would fall into oblivion and not be retrieved until decades later, when it became part of the then Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno.

Macro photography reveals valuable information on the application of colour by a young Picasso beginning to challenge traditional methods.

Therefore, it is worth noting the details on the sitter’s face, particularly the short, brisk and deliberate red brushstrokes on her mouth, as well as the lively impastos applied with the brush on her neck , in a colour that was no longer part of the artist’s palette. The application of paint on wet paint creates fusions of colour within the same stroke; this can also be perceived on the borders of the dress.

A magnified detail on the bottom left corner shows how this canvas was attached to another piece of fabric in a past restoration, a process known as relining.

The application of ultraviolet light in Mujer en azul reveals previous interventions which conceal abrasions on the dress and right arm of the model.

This technique enables us to distinguish between original paint and chromatic additions, known as retouching. This information was particularly useful when the work was restored in 2012 as it enabled the original colour underneath these additions to be recovered.

As we can see on the face, where the layers of paint are lighter, the lack of a prior compositional drawing provides important details regarding Picasso’s swift and direct method. Equally, with the infrared radiation technique we can identify the added stuccos used in previous restorations to even out paint losses via the white that shows up in the image.

X-rays offer interesting details with respect to the work’s support. Upon magnifying the image, the weaving and warp of the linen canvas Picasso used are fully defined in detail. On the edges, we can see the grain of the stretcher wood tautening the work, and even the staples that fasten the fabric to the side.

Furthermore, with this study we can once again appreciate Picasso’s workmanship in applying colour with sweeping, highly fluid gestural movements. The bow around the sitter’s neck also catches the eye given that, prior to the bluish-green seen today, it could have been decorated with dots.

The x-ray, moreover, thoroughly determines the extent of damages to the painting, the scope of the craquelure and losses to the pictorial layer. An essential tool which, combined with the other technical studies, gives the restorer clues to gain an understanding of and intervene in the works by fully respecting the original.