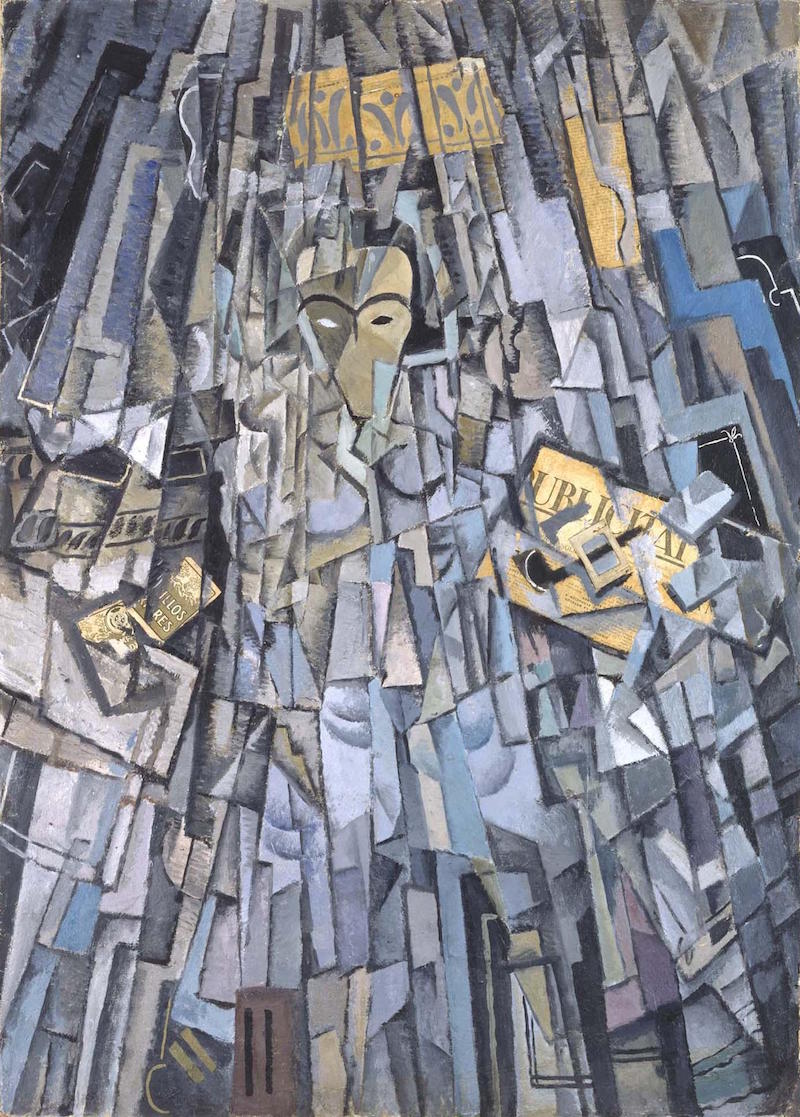

Salvador Dalí

Cubist Self-Portrait

L'homme invisible (The Invisible Man), started in 1929, is one of the first works Salvador Dalí made in which his paranoiac-critical method materialised via the use of double images. In his article The Rotten Donkey, published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, the artist described these images as: “the representation of an object which, without the slightest figurative or anatomical modification, is, at the same time, the representation of a completely different object”. A visual language with precursors in Arcimboldo’s teste compostes (composite heads) and the anthropomorphic landscapes of Joos de Momper, which were popular around 1600.

At first glance, an oneiric scene with a marked perspective appears populated with fantastical figures and architectures, yet with the effect of an anamorphic perspective it reveals the image of a man sat, hands on knees, akin to an Egyptian colossus. In his choice of some of these figures, Dalí draws on images which would run recurrently through some of his other works, for instance the representations of Gradiva and the family of Guillermo Tell. Some of them are, in turn, double images, for example the lying woman-horse that appears in the top-left corner.

Despite the work being unfinished, a macro-photographic study enables us to corroborate how the artist revelled in the details, executing them with sublime precision. The support he used was an industrial canvas whose white priming can be seen in the areas where the paint is lighter. He later sketched the drawing using graphite and ink.

The compositional outlines are visible in many areas, for instance on the horizon, where a group of lines converge in a vanishing point and a new sphere appears only as an impression.

Furthermore, the strange construction of concave and convex edges, to the left of the invisible man’s face, is shaded with swift lines of ink, a preparatory step before the paint layer which, in this case, was never applied in this unfinished work.

In the cluster of figures that appears on the bottom right we can see lines of graphite and paint, showing the possible variations to the composition that Dalí never executed.

This technique offers a detailed study of the types of craquelure that appear on the surface; specifically, in L’homme invisible we can see cracks in black tones.

Exposing the canvas to ultraviolet light reveals significant information on the varnishes and outermost layers of paint. Chiefly in the darker areas, we can discern a non-uniform varnish, the uneven application of which formed streaks. This was a customary technique used by the artist, who saw varnish as more than simply a protective layer and used the substance as an intrinsic part of the composition. Interestingly, comparing this phenomenon to the macro-photography study reveals uneven areas of varnish that are not visible to the naked eye.

In three areas this use can be better distinguished: on the black background which creates the shadow cast by the pedestal; on the floor and the black steps at the bottom; and in the gallery of arches and pillars crowning the building to the right of the central image.

Furthermore, the study with this light helps to define the chromatic retouching. In not being original and executed with a different material, still indiscernible in natural light, it responds to fluorescence differently and appears darker, as with the retouching on the left leg of the invisible man.

Preparatory drawings were commonplace in Salvador Dalí’s artistic practice. In this instance, infrared reflectography means we can see graphite lines hidden to some degree under layers of colour. We can perceive the initial lines, applied fluidly, which correspond to the first compositional sketches, and a more highly crafted drawing which includes graphite shading.

For instance, we can make out a geometric grid and different modifications to the area on the hands of the central personage.

Equally of note are the multiple compositional outlines of the pillar, located to the left of the invisible man.