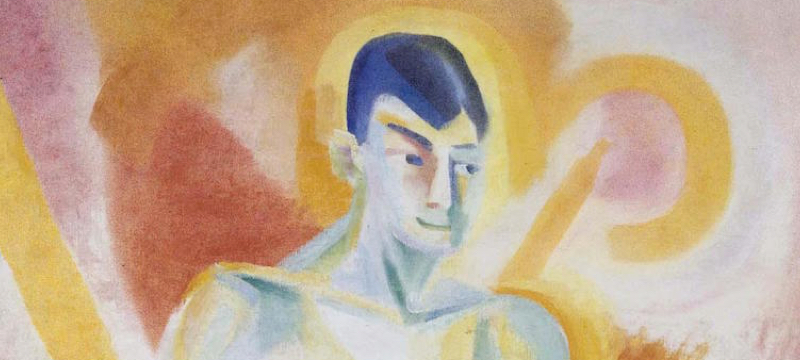

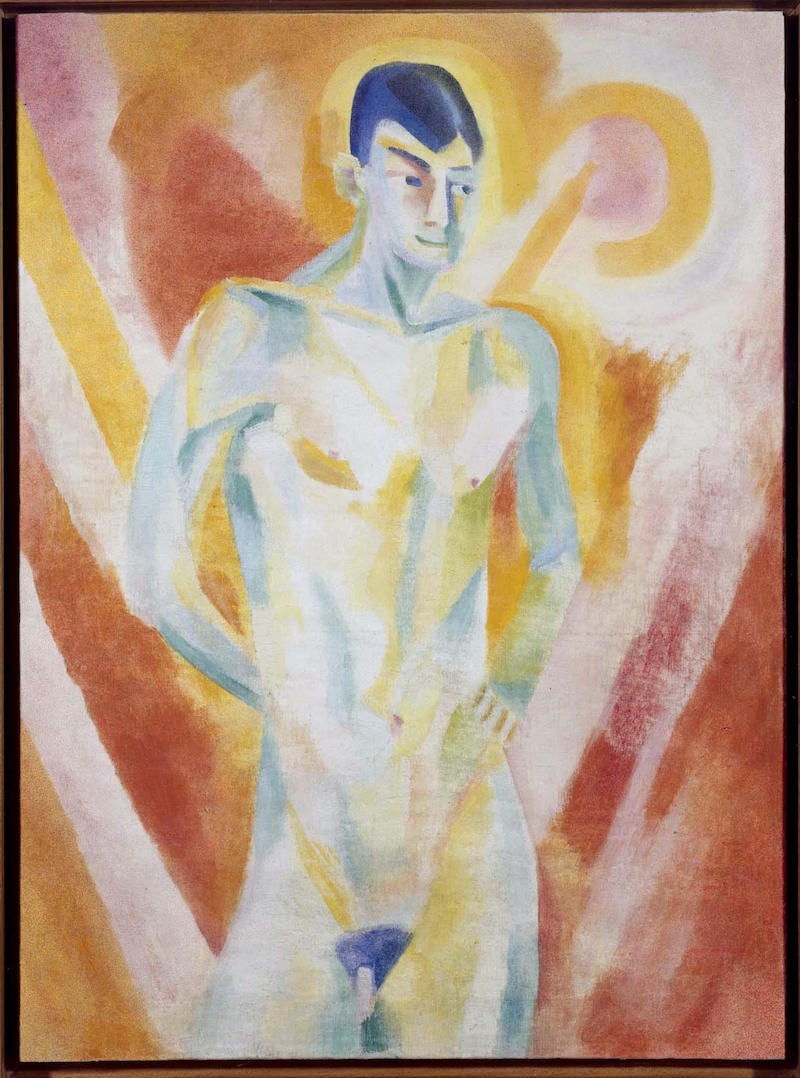

Robert Delaunay

Le gitan (The Gypsy)

Robert Delaunay was deeply involved in developing Cubism in France with a personal style named Simultanism, that would run into abstraction around 1912. During the First World War he moved between Spain and Portugal with his wife, the artist Sonia Terk-Delaunay, and together they singularly worked in avant-garde circles in Madrid and Barcelona, in particular with the Ultraist group, Ramón Gómez de la Serna and Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company.

During his time on the Iberian Peninsula, Delaunay experimented with a return to figuration, yet without losing sight of the vibrant colouring and abstract forms of his previous work. With a starting point around visits to the Museo del Prado, he produced a series of paintings based on works from the Madrid gallery, among them Le gitan (The Gypsy), inspired by El Greco’s Saint Sebastian. In this piece, Delaunay deconstructs the figure of the model into a Cubist idiom, placing it before an abstract background with geometric forms characteristic of Orphism.

In Le gitan Robert Delaunay’s experimentation was significant. With vibrant colours, characteristic of his technique, he mixed different mediums, such as wax crayons and colours in water to obtain such a unique surface. Moreover, macro photography reveals a dynamic play with the lightest and most vibrant layers and more matter-based lines, revealing traces of brushstrokes.

When carefully observing the painting, areas in which the original paint was lost and retouched with colour can be discerned, and, although these can be seen broadly across the entire surface, they become sharper when the area of the neck and chin is enlarged.

In the study with visible light, the different types of craquelure are examined on the pictorial layer, for instance on the area of the chest, in order to keep an eye on any further development.

Photography with oblique angle light highlights the relief of the surface. On one side, the volumes of the vertical threads corresponding to the canvas weave are noticeable; on the other, the small protrusions across the surface of the canvas, relating to the fabric or, in some instances, tiny colour impastos.

Moreover, this type of lighting underlines the brushstrokes with a greater concentration of matter. As the image is zoomed in upon, the perfection of the traces left by the brush as it drags the paint are depicted, as is the subsequent tear caused by the craquelure, observed in the impasto on the gypsy’s right ear.

Ultraviolet light reveals a host of losses which have been reintegrated and which contrast with the dark-blue colour with regard to the pictorial layer. This type of photography is a key tool for restorers and conservators in thoroughly assessing the extent of the damage and to easily differentiate between the original and any addition.

The image taken through infrared reflectography reveals a series of vigorous lines and curves that run through the work horizontally. These brushstrokes were carried out by the hand of the artist and were made as he prepared the white priming layer.

This technique reveals lines from the rough preparatory sketch Robert Delaunay used as a composition drawing, as we can see on the right armpit of the gypsy.