Joan Miró

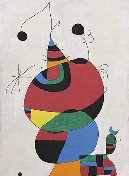

Woman, Bird and Star [Homage to Picasso]

![Joan Miró: Woman, Bird and Star [Homage to Picasso] Woman, Bird and Star [Homage to Picasso]](/assets/img/obras/AS03162.jpg)

Upon his death, Joan Miró insisted Pablo Picasso was a fascinating man, and for the Catalan painter he would be a reference point from the outset of his career, which began with a distinct revision of Cubist figuration, to the end, when both struck up a fraternal and devoted friendship. Picasso, in kind, admired the work of the Barcelona artist, ten years his junior — as André Breton recalled, it was that particular interest in Miró’s painting that brought him closer to Surrealism. At the Spanish Pavilion of the Paris World’s Fair in 1937, both exhibited work, producing two large-scale mural paintings in support of the legitimate regime of the Republic: Picasso with Guernica, and Miró’s now-lost El segador (Paysan catalan en révolte) (The Reaper [Catalan Peasant in Revolt]), with both pictures becoming, from the 1950s onwards, two touchstones for Spanish artists living under the dictatorship.

After a prolonged execution process, Joan Miró deemed this large-scale painting to be finished on the day his friend died, and on the back included a subtitle in Catalan, the language in which the two communicated with one another. Femme, oiseau, étoile (Homenatge a Pablo Picasso) (Woman, Bird, Star [Homage to Picasso], 1966–1973) is a painting with overt references to figuration, appearing sharply in the form outlined on the white background, in which the contrast with the planes of colour stands out, acting as an independent, not mimetic, component in the work. The composition focuses on three essential figures in Miró’s symbolism: the woman, alluding to the link of humans with the roots of the earth, the bird and the star, which symbolise poetic and spiritual attraction and are represented on either side of the central figure.

The picture is defined, moreover, by the strength of the white background, which is treated with all the richness and complexity afforded by the quality of the material and adroitness of execution. Upon this brilliant background emerges the large female figure, with forms as broad as a Neolithic sculpture, and built as a gigantic collage of flat colours. As William Rubin highlighted when referring to Femme aux trois cheveux encerclés d’oiseaux dans la nuit (Woman with Three Hairs Surrounded by Birds in the Night, 1972) — with which this picture forms a pair — Miró followed the colour palette of the traditional whistlers from Mallorca or Siurells. The contrast between the linear signs of the star, hair and headdress in comparison with the full, colourful and flat forms of the woman and the bird perched on her, shaping a hybrid personage, characterise this great emblematic composition in Miro’s mature work and the Museo’s Collection.

Using macro photography with visible light we can appreciate the technical richness of Joan Miró’s execution by observing different parts of Femme, oiseau, étoile (Homenatge a Pablo Picasso). Firstly, it gives us some idea of two phases in his creative process: an initial stage in which he marks out the black contours and a subsequent one in which he works with the fields of colour. This distinction is made possible because, upon zooming in on the central figure, the layers of colour overlap the black lines at many points, and, similarly, we can note the different densities in the layers of colour: the central green area, where the background shows through and underscores the imprint of the brush, is, for instance, not as dense as the red areas.

On the background of the painting the artist plays with different white tones. On the priming, a light yellow colour and frequently exposed, he overlaps vigorous strokes, in this instance with a bluer shade.

As the image is enlarged, macro photography reveals the multiple pores produced when the priming layer was dried and transferred over to the layers of paint. This is especially prevalent in the red and orange parts.

Additionally, it reveals a grid of craquelure affecting a large part of the pictorial surface, and worthy of analysis is the white on the bottom right of the canvas, where certain micro-fissures are covered in paint — also white. This would suggest that the artist’s own intervention on the work took place on the second date he wrote on the back of the canvas: 1973.

Certain colours, depending on their nature and composition, are shown in a different tone and opacity after being exposed to ultraviolet light. In this painting it occurs with the red, which under ultraviolet light appears as black-violet, and the orange, which turns brown. Furthermore, this technique gives greater definition to the traces of the brushstrokes in colours such as green, blue and yellow.

In particular, it is worth examining the white background under ultraviolet light and comparing it with photography with visible light. Due to the way different materials respond, we can distinguish the priming layer in a fluorescent green tone and the emphatic strokes of paint in blue-violet. This contrast provides valid information on how the artist managed to get the white background to vibrate.

In the central part of the figure, infrared photography enables hidden elements under the paint to be examined, for instance the dripping long vertical lines and other lines in the shape of an X.

Likewise, moving through the layers, those overlapping the initial black contour are clearly defined, as seen in the two red fields on the arm holding the bird.

![Woman, Bird and Star [Homage to Picasso]](/assets/img/compartir/femme-oiseau-etoile-homenatge-pablo-picasso-mujer-pajaro-estrella-homenaje-picasso-joan-miro.jpg)