Salvador Dalí

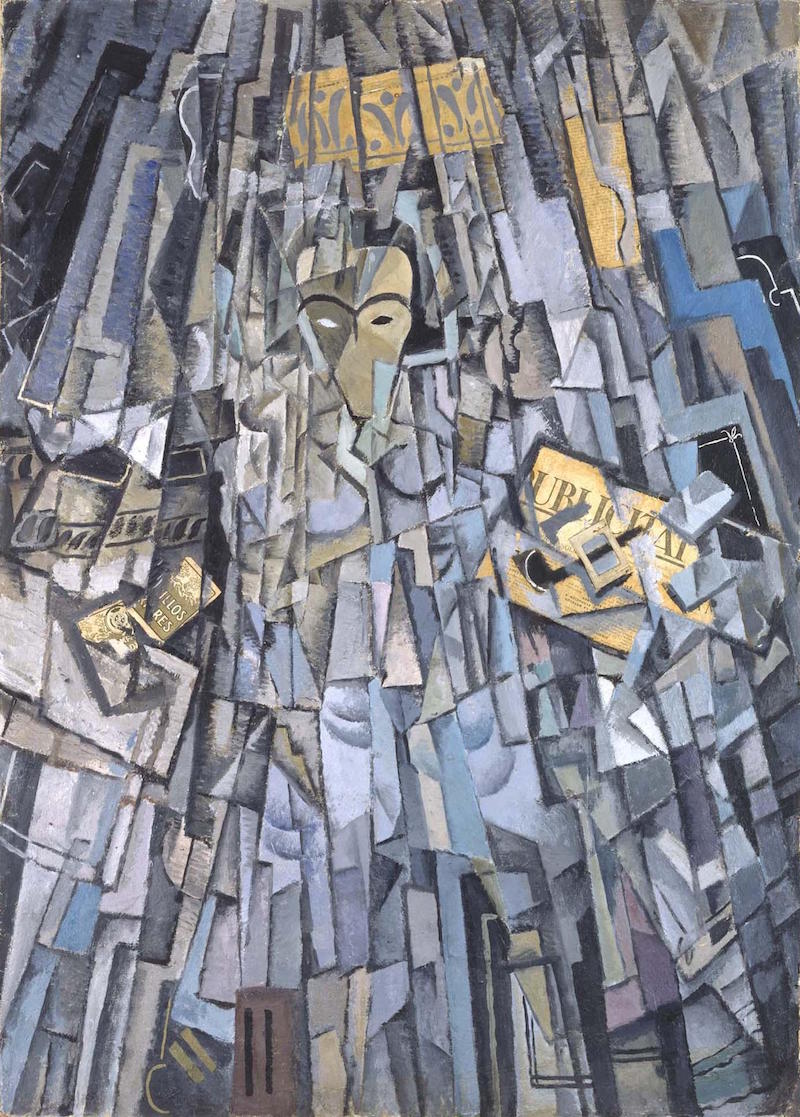

Cubist Self-Portrait

Salvador Dalí’s encounter with Cubism began in 1922 while he was a student in Madrid and after reading the magazine L’Esprit Nouveau, which his uncle managed to obtain for him from Barcelona. For the five or so years he made Cubist works, Dalí experimented with different styles, influences and techniques that had materialised during the movement’s fifteen years of life, although ultimately the tenets of Purism, a more recent version of Cubism, would resonate more.

His 1923 Autorretrato cubista (Cubist Self-Portrait) serves as a good example to demonstrate that crossover of influences. Thus, in his portrait-mask, with its African aesthetics, Dalí inserts a composition inherited from the Analytical Cubism Picasso was working on around 1910, adding the papier collé technique, introduced by Picasso and Braque in 1912.

Photography with visible light enables us to gain insight into the technique Dalí used in this emblematic self-portrait, an early piece in his Cubist period.

By directing the zoom towards the sides, we can see that the support used is not canvas but rather paperboard.

Dalí would affix a number of elements to the support, for instance newspaper, cigarette paper and a slide frame, making it a collage, an innovative technique specific to Cubism and introduced from 1912 onwards.

He would later create the black lines of the composition, forming a triangular structure that splits the surface up into small geometric spaces.

These spaces were filled with short brushstrokes in a chromatic palette with cold colours.

Dalí also underlined certain black lines — for instance his own eyebrows — to lend greater weight to this identifying strand of his portrait.

Furthermore, macro photography provides information about the conservation state of the work. On the grey surface underneath the cigarette paper, to the left of the figure, we can make out a series of vertical cracks, fissures on the pictorial layer which are repeated in multiple white, grey and black areas.

In this kind of study the light stresses the relief of the work. In this instance, it offers a different view of the brushstrokes, impastos and elements Dalí added to the composition.

Such a vigorous imprint of the brush and plays with delineation are striking, with the artist moving the brush in different directions, at times using energetic curved movements to build different layers of colour. This can be seen on the face.

It is also worth analysing in detail the newspaper to the right of the figure: the coarseness of the paper, a crease running cross-wise and a large crack in the paint that corresponds to the upper edge of the newspaper, where we can also see a minor loss of paint.

This tool also enables us to detect potential intrinsic problems with the work’s structure. On the one hand, small dots in which elements of the collage show an emerging lack of adhesion; and, on the other, the problems of exfoliate on the paperboard, perceived on the side.

Observing Dalí’s Cubist self-portrait under ultraviolet light demonstrates significant details related to previous restoration treatments. The different nature and age of the materials conditions its response to light, which is why the inconsistent strip on the bottom end, corresponding to colour retouching, appears yellowy and clearly delineates the portrait.

On the lower edge of the painting these reintegrated losses highlight a greenish-grey colour — lighter than the original — which appears in blue and violet tones. This, therefore, makes it easier to narrow down the real extent of such chromatic reintegrations.

In this case, the study of the work according to the infrared range does not provide significant details of whether there is a preparatory drawing or prior compositional outline.

Nevertheless, it is also worth looking more closely at the newspaper cuttings. The letters printed on the paper appear to be defined, making them easier to read and demonstrating, in some areas, the printed letters on the back.