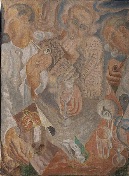

André Masson

The Smokers

The traumas of the First World War prompted André Masson to resume an artistic practice that had been brought to a standstill by the conflict. This new phase, undertaken in the early 1920s, would be heavily influenced by the work of Paul Cézanne, André Derain and Juan Gris, a synthesis Masson would realise and give rise to a distinctive and decorative Cubist style, the use of curved and winding forms affording a sensuality that was enough to catch the eye of André Breton, who would appeal for him to become part of the Surrealist group he created in 1924.

In 1921 Masson started to make a series of works with a common theme running through: the representation of different men together around a table, iconography taken from Derain’s work Drinker (1913–14), and a theme he would use assiduously from 1923 to 1924. These groups of figures drinking, smoking, playing cards or gambling can be interpreted as memories of life in the trenches, and the presence of a pomegranate on the table acts as a symbol of both life and death.

In Les fumeurs, Masson explored a new technique, combining the imprint of Cubism with a renewed allegiance to Surrealist inclinations. Macro photography reveals traces left by both influences on the painting’s different stages of creation as it uncovers the minutiae of how the work was executed.

In the area of the hand holding the glass, located in the centre of the composition, we can make out very fine linen fabric, with a light ochre base — the priming – upon which Masson sketched out in pencil the winding, curving lines he used to determine the main personages, as verified in the contours of that particular hand. The artist later applied very thin layers of colour, deliberately leaving in view pencil lines and the priming.

Over time, the tautness caused by Masson’s artisan priming layer explains the micro-craquelure, which today spreads across the entire pictorial surface and is visible when browsing with greater magnification.

Finally, the full zoom reveals small white dots corresponding to micro-losses, where the absence of paint exposes the colour of the underlying white primer and constitutes the first layer in contact with the canvas.

Macro photography with oblique angle light enables the way in which the artist worked and his brushstrokes to be analysed in greater detail.

At first glance, the flawless weave of the canvas linen stands out. With greater magnification, the grooves left by the brush in the application of slightly denser paint layers can be distinguished.

Moreover, the use of oblique angle light exposes the grid of craquelure which affects the entire surface of the work and is caused by incompatibility between the materials Masson used in the different layers.

Under ultraviolet light we can see the fluorescence of the priming, on view between the layers of colour. With this kind of light, the work is seen in a bold cerulean blue, whereas with natural light it is more of an ochre colour. Although the phenomenon appears across the whole painting, it is also interesting to compare the photography with visible light and ultraviolet light in the area of the pomegranate.

Elsewhere, this kind of lighting highlights the sheer number of paint losses that have been restored and verifies how the chromatic reintegration precisely redresses the lack of original paint. This reintegration shows up as dark-blue dots and was carried out with watercolour.

Although the underlying drawing lines can be discerned with natural light, the infrared image reveals them with greater precision, allowing for an appreciation of the evocative design of curves the artist made with a graphite pencil. André Masson used this blueprint of undulating forms as a guide to apply light layers of colour.

The comparison between infrared photography and visible light photography underscores the importance of the preparatory drawing in details such as the pomegranate, the faces and the hands of the personages depicted.